“While he was standing there looking at that door, he was getting an erection.”

This is Alfred Hitchcock describing to François Truffaut the iconic scene in Vertigo where Scottie waits for Judy to emerge from the bathroom. Earlier in the day, under pressure from Scottie, she bleached her hair and put on a grey suit. She has only to put up her hair and she will be identical to the fallen Madeleine. A turquoise light falls on the room and she emerges as if out of mist. The way he looks at her, the way he touches her, they way they kiss, in every sense he has risen.

I was initially moved to write this mini-essay by an exchange on the r/redscarepod subreddit debating the horniness of David Lynch.

In this thread ‘milfbong666’ suggests that Lynch’s portrayal of sexuality is not in line with someone who is horny. While the sex scenes in Mulholland Drive are very erotic, this is tempered by the terrifying loss of self experienced by Betty/Diane. In Lynch’s TV series Twin Peaks the kidnapping of mischievous seductress Audrey is genuinely distressing, and forces the audience to switch quickly from arousal to concern. It’s precisely these juxtapositions of the sexy and the disturbing that give Lynch’s films balance and complexity.

The horny filmmaker, like Scottie in Vertigo, feels attached to a specific outcome. The woman must wear a particular dress, she must put her hair up a particular way, she must be in love with me, and only me. Hitchcock’s entire world view is controlling, masculine and voyeuristic. This is not a value judgement. These traits are prevalent in human life. They are tendencies experienced by all straight men to differing degrees. In this regard art must fulfil its fundamental duty of truthfulness.

So who’s horny and who is not? Rainer Werner Fassbinder lingers lasciviously on El Hedi ben Salem’s firm brown torso and Hanna Schygulla’s pale, plump chest. Michelangelo Antonioni wallows in Monica Vitti’s sultry despair.

Fassbinder copping a feel of co-star Hanna Schygulla in his directorial debut Love is Colder than Death.

Céline Sciamma uses the device of portraiture to turn up the heat in Portrait of Lady on Fire, creating a tantalising 90 minute buildup before our protagonist finally gets her hands on the forbidden fruit.

A flourish of desire remembered in Portrait of Lady on Fire

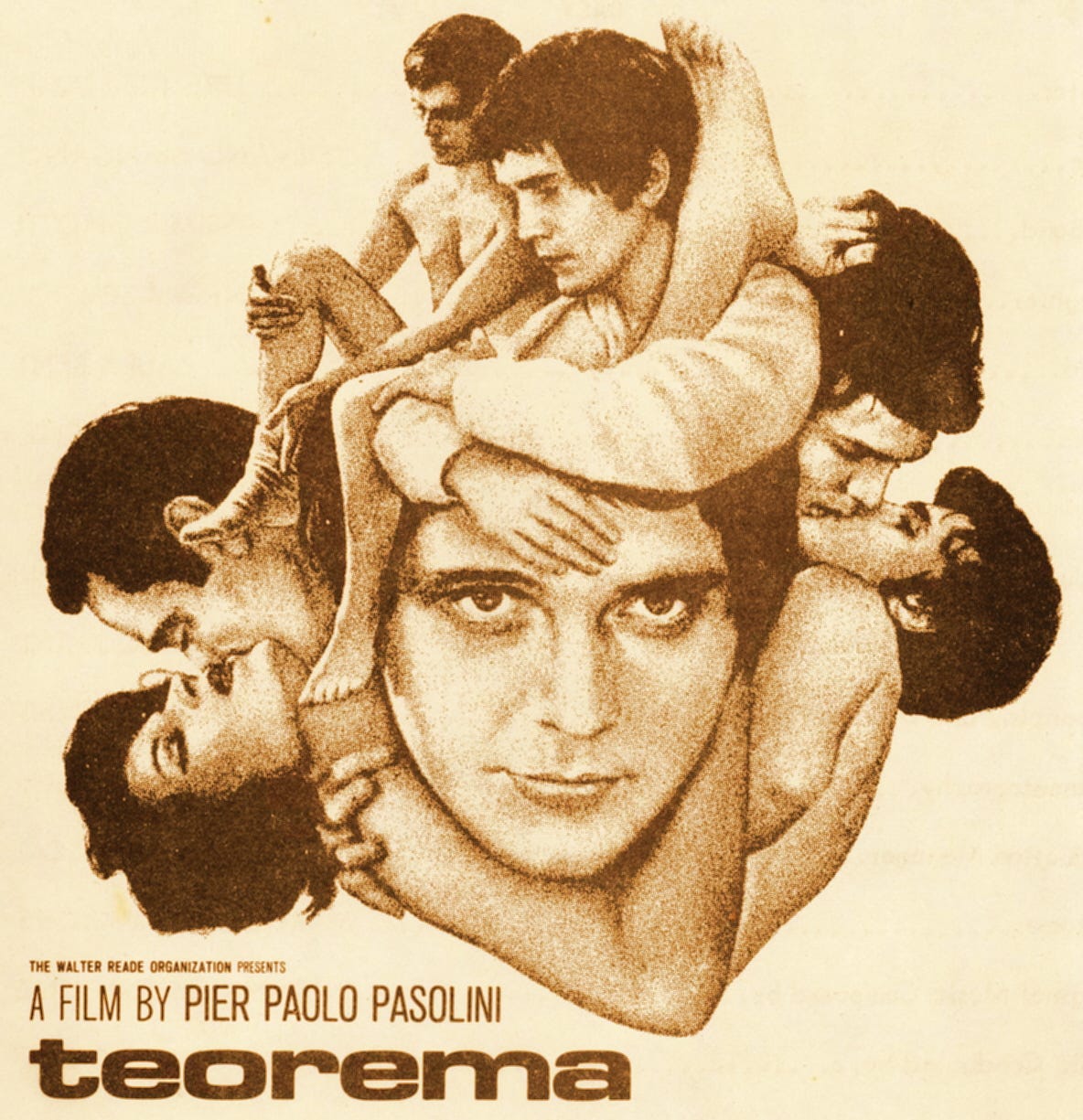

Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl luxuriates in the dodgy seduction of virginal Elena by the coercive Fernando (a fixation further explored in her subsequent meta-film Sex Is Comedy). Explanation is not required for human tripods Pier Paolo Pasolini, Walerian Borowczyk and Gaspar Noé. Watching these films engages the viewers libidinal impulses. They makes us hard, wet, excited, needy.

A delicious poster for Pasolini’s subtle tale of seduction Theorem.

On the other side of things there are the chaste directors. Werner Herzog’s predatory anti-heroes are plenty virile but all their orgastic energy begins and ends at the death drive. Aguirre, Noseferatu and Timothy Treadwell (Grizzly Man) all sublimate their libidos into a dance with death.

The husband-and-wife scenes in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris are sterile, while in Stalker the conjugal dynamic is irritable and anguished. The scene in The Sacrifice where Alexander ‘lies with’ his maid Maria (a witch, apparently) as a last-ditch attempt to save humanity from nuclear holocaust certainly wouldn’t last long on PornHub. Memories of overpowering mothers give Tarkovsky’s films plenty of Freudian bite but sexual gratification is always overshadowed by spirituality.

‘Maybe not tonight, darling’ - Tarkovsky’s Solaris

Robert Bresson’s blank-eyed ‘models’ (his clinical euphemism for actors) seem indifferent to sexual pleasure. Bresson’s kisses, like the one made through prison bars in Pickpocket, are beautiful and tender, but never sexy. Other serious European auteurs such as Bruno Dumont, Michael Haneke and Carl Dreyer also seem above lust.

Dejected students in Bresson’s The Devil, Probably

The non-horny filmmaker seems to put our personal desires into perspective. Things just are. Stories of love play out like the events in a pre-ordained sequence, like battles in an ancient myth.

The horny director puts desire centre stage, showing us where to look, what to like, sometimes catching us out. Paul Verhoeven’s extravagant thrillers lure us into throws of fleshy ecstasy, moments before taking an ice pick to our necks.

The chaste director obtains a godlike elevation from human self-consciousness, a kind of mindfulness. In Lynch’s case this feels connected to his much-proselytized practice of transcendental meditation. But it’s also borne out in the accounts of his female actors, many of whom spoke out in praise of his empathy on-set. Despite making some of the weirdest, most sexually violent films of the Western canon Lynch’s reputation is unblemished. As one Redditor warned ‘It’s the more conventional filmmakers you have to watch out for’.

David Lynch directing Naomi Watts in Mulholland Drive, a film which depicts exploitation in the film industry.

Why does the horny binary feel pertinent? Creativity and sexual desire exist in symbiosis. They are competing drives which easily sublimate into one other. When I write screenplays, and especially when I share early drafts with colleagues, I’m acutely aware of the thin line between filmmaking and fantasising. What we see VS what we want to see. Cinema is uniquely placed to explore this is point of tension - as Hitchcock does brilliantly in Vertigo. As a writer/director I have the power to draw my dreams with other people’s bodies. It’s a privilege to do so and comes with huge responsibilities.

We’re clearly at a crossroads regarding horniness. The film industry is justifiably under pressure to reform and shibboleths of male genius are being torn down. But we shouldn’t learn sexual repression from stories of sexual exploitation. Without the honesty of raw desire, cinema tells us nothing of the human experience.